From Texts to Tiles: Turning Clues into Coordinates Across the Amazon

A Scalable Pipeline for Amazonian Archaeological Discoveries

Preface

This is part of the submission of the Kaggle OpenAI-to-z competition my ex-colleague Naomi and I teamed. Over the past two months, we participated in this research-driven challenge focused on identifying previously unknown archaeological sites within the Amazon biome, primarily in Brazil and its surrounding regions. Using open-source data—such as satellite imagery, lidar, historical accounts, and indigenous knowledge, this challenge aimed to uncover evidence of ancient civilizations and contribute new insights into Amazonian history. The work was supported by AI tools, including OpenAI models, and emphasized rigorous, reproducible research to support archaeological discovery and preservation. This brief project blog will show the data we used, method and approaches we took, as well as the path that leads to the final submission.

Overview

We began our investigation with the most obvious idea—look directly at Landsat imagery and try to spot archaeological sites. But very quickly we realized that this approach doesn’t scale. The Amazon rainforest spans over 6 million square kilometers. Scanning tile-by-tile with no guidance is neither efficient nor tractable. We needed a better way to prioritize where to look.

So we flipped the question: instead of asking “where are the undiscovered sites?”, we first asked “what do the known sites look like in satellite imagery?” This gives us a Bayesian lens: rather than trying to model the probability of a site existing from scratch, we use documented sites and their surrounding features to build an informed prior. Our new goal: discover new sites by first confirming known ones, then generalizing from them.

Step 1: Anchoring with Historical Accounts and Satellite Imagery

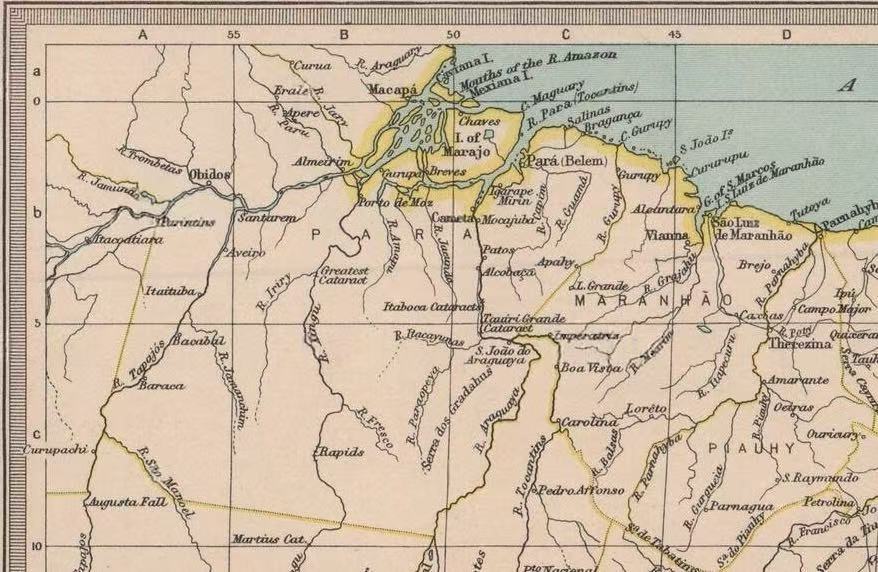

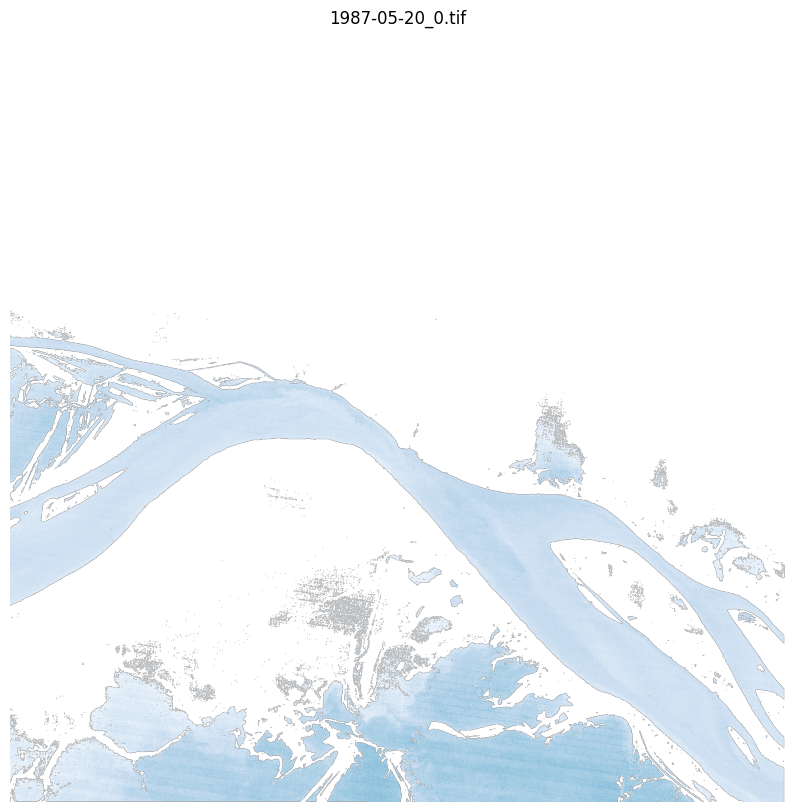

Our first experiment focused on Óbidos, a known colonial fortification mentioned in The Amazon and Madeira Rivers (1854). The book describes specific spatial features—a river narrowing, a current, and a small fort bypassed via a high-water lake. These details helped us triangulate the general area.

To minimize confusion from modern urbanization, we aligned this with pre-1990s Landsat imagery, where terrain and water channels were less altered. We successfully matched both visual features and structural patterns to the fort described in the book, confirming its historical position.

Once located, we expanded our search in a radius-based fashion, scanning nearby terrain patches to identify further sites with similar features. Several river-adjacent clearings and possible mound patterns were flagged by GPT-4 Vision agents for further review.

Step 2: Turning Text Into Coordinates—at Scale

After verifying that we could geolocate known sites, we sought to automate this process. We built a pipeline that takes historical texts, books, and indigenous records, parses them with GPT-4, and extracts:

- Location hints and geospatial descriptors

- Known landmarks or proximity constraints

- Keywords relating to site function (e.g. “military”, “gathering”, “mounds”, “cemetery”)

These were then converted into WRS-2 or MGRS tiles, enabling us to programmatically request satellite data for only the most relevant areas. We call this pipeline Text-to-Tile, and it forms the backbone of our strategy.

Step 3: Internalized vs Externalized Pattern Matching

We explored two main GPT-driven methodologies for evaluating the satellite patches:

- Language-based: where the LLM is given a description of what to look for (e.g., “a fort should be near a sharp bend in a major river, with cleared land and possible geometric patterns”), and asked to verify if these features are present in the image.

- Encoding-based: where we show the LLM example images of verified sites (like the Obidos fort), then ask it to find visually similar patterns in nearby or newly suggested regions.

This dual approach allowed us to:

- Operate even when documentation is minimal (via internal reasoning),

- And scale up detection via visual analogy when strong examples are available.

Step 4: Building a Platform, Not Just a Pipeline

While many participants might stop at isolated discoveries, our work aimed to enable future archaeologists and researchers. We invested heavily in designing a reusable, extensible toolkit that can:

- Overlay and normalize satellite imagery (Landsat, Sentinel)

- Stack elevation and surface reflectance maps

- Accept natural-language input for site searches

- Generate structured GeoJSON or visual outputs

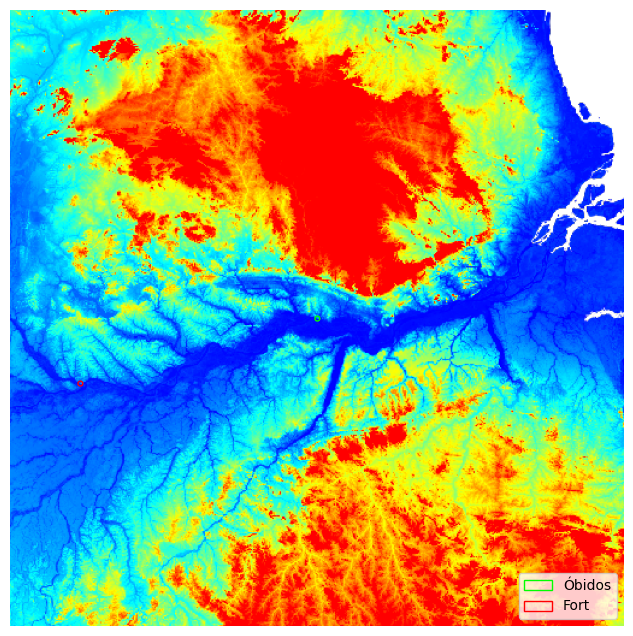

Our pipeline doesn’t just propose hypothetical sites read from esoteric ancient books. It tries to verify them by multiple sources, and can be used as a mechanism to effectively search through region of interest. This was the initial take, but we were restricted to the Obidos region at the time. To enable the scalability of the pipeline, we then tried to extend it to arbitrary site locations, and used Sentinel-2 for better resolution data. Because of limit of time and resource we focused mainly on the Santarem site, which is about 106km from the urbanized Obidos site.

Step 5 [Future Works]: Seeing the Hidden Graph — Pattern Networks

Up to this point, we treated discoveries as individual points. But civilizations don’t grow in isolation. Forts, trade routes, agricultural zones—they form networks. Our next step is to examine:

- Proximity networks: Are certain classes of sites more likely to occur near each other?

- Environmental signatures: Are certain terrain + river + elevation configurations predictive of site clusters?

- Chronological gradients: Can we predict directional flow of civilization via vegetation regrowth?

These analyses are underway, and our platform is already capable of supporting such model layers.

Our work moves beyond a single discovery. We’ve built a scalable research assistant—an LLM-powered, geospatially aware system that helps archaeologists move from texts to tiles to truths.

With more time, more data, and deeper collaboration with experts, this approach could redefine how we uncover the past, saving enormous search costs.

Appendix

We utilized the following datasets:

- Landsat OLI-2/TIRS-2 series (satellite imagery)

The preprocessing of Landsat imagery follows a structured pipeline involving region selection, band selection, and data normalization. The general steps are as follows:

1) Define the Region of Interest (ROI)

A specific geographic area is selected using coordinates. For instance, the region around Óbidos with a 15 km extent can be defined as:

obidos_15km_region = ee.Geometry.Rectangle([

55.5865, # West (-55.519 - 0.0675)

1.9685, # South (-1.901 - 0.0675)

55.4515, # East (-55.519 + 0.0675)

1.8335 # North (-1.901 + 0.0675)

])

2) Select Spectral Bands

Before performing any analysis with Landsat imagery, it’s essential to select the relevant spectral bands. Landsat satellites capture reflectance data across multiple wavelength regions (e.g., blue, green, red, near-infrared, shortwave-infrared, thermal). However, not all bands are useful for every type of analysis.

Each band corresponds to a specific range of the electromagnetic spectrum and highlights different land features:

- Visible Bands (Blue, Green, Red): Capture what the human eye sees; useful for true-color imagery and basic visualization.

- Near-Infrared (NIR): Highly reflective for healthy vegetation; essential for vegetation indices like NDVI.

-

Shortwave Infrared (SWIR): Sensitive to water content in soil and vegetation; useful for water detection (e.g., NDWI), burn scars, and drought monitoring.

3) Normalize and Export Tiles

The selected bands are normalized to standardize pixel values across images. The processed tiles are then exported for further analysis.

- Elevation data. The image below is an example of elevation image, region with same color has the same elevation. Elevation data are converted into different color pixels.

- Harmonized Sentinel-2 MSI. This data provides finer resolution (as high as 10-15km) than Landsat images.

- Landsat WRS 2 Descending Path Row shape file (.shp). It is used to map coordinates to tile row IDs for efficient region localization.

- Historical texts: We use Google Search API to get URL for related historical text given key words and manually download 4-5 books, paragraphs for historical reference. Important ones include The Amazon and Madeira Rivers, The Amazon Várzea: The Decade Past and the Decade Ahead, Gutenberg, the Archeoblog.