Urban Exploration I: What is it, and Why

On a normal Tuesday, Oct. 17th, 1989, an earthquake of 6.9 Mw magnitude, originated 19 km below ground surface, 16km northeast of Santa Cruz, swept from Loma Prieta Peak all the way to the north of San Francisco Bay, resulted in thousands of casualties. Besides over 4,000 landslides and broken sections of the SF-Oakland Bay Bridge, this disaster also severely damaged the Southern Pacific 16th Street Station in west Oakland, 90 kilometers away from the epicenter. Originally built and opened in the late 19th century, this station has served as the main rail link for points north and east of Bay Area. As a minor consequence of earthquake aftermath, comparing to other horrendous ground failures, the railway station continued its operation in an adjacent building, until Aug 21, 1994, when the Coast Starlight and California Zephyr made their last stops. The station was then closed, and the railway tracks were removed during the construction of I-880 highway, detaching it from the Bay Area rail network. The tech boom in the coming era sent the station into oblivion: forgotten by the locals, succumbing to its desolation.

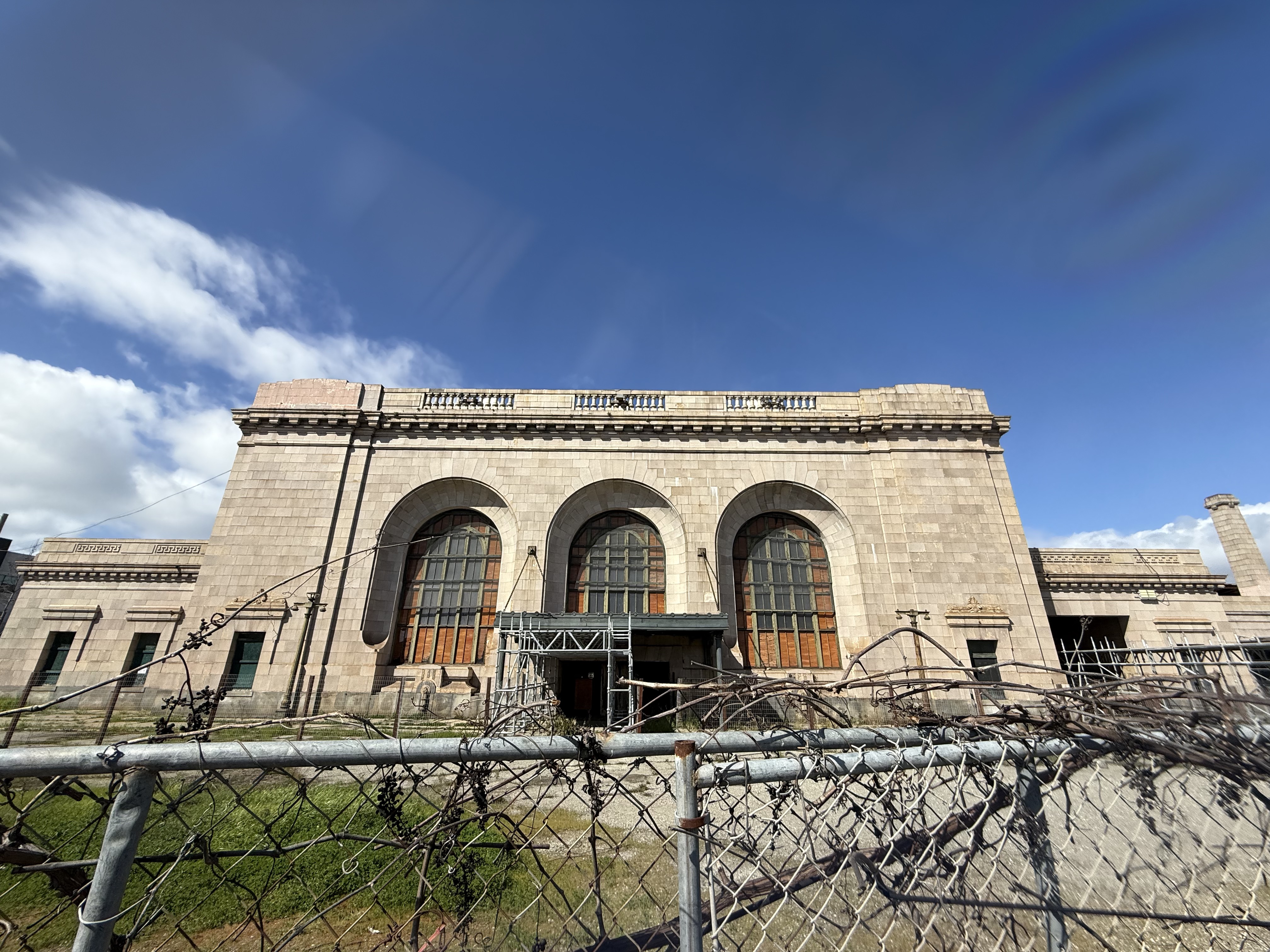

Today, the station is surrounded by barbed wires and fences, with wood planks sealing all entries and windows, weeds and branches encroaching every inch of its perimeter. Two camera poles with megaphones attached surveil the front and back side of the building, warning signs intimidating potential intruders. Next to it are brand new apartments and flower farm, casting a giant contrast between the two worlds. We were not expecting such high level of security upon arrival. There were three holes in a section of the fence, but the camera behind it made it merely impossible to enter the main hall without being detected.

This is what urban exploration, or “urbex” for short, is about: the practice of entering vacant, uninhabited, or abandoned sites, for the purpose of exploration and documentation.1

It is a creative process, that requires location searching, information gathering, plan making, mixed with a sense of defiance to the authority, as well as the adrenaline rush facing the unknowns. It is a highly interdisciplinary field, where knowledge in history, social science, geoscience, dendrology, architecture, urban engineering, economics, and even biology are preferably required, for safe and fruitful explorations. Urban exploration, while hovering on the edge of legality, with risk of trespassing, does not equivalent to vandalism. Different from tagging (graffiti) or squatting (illegally residing in), it focuses on documentation and the experience itself, rather than modifying the state of the sites.

The term “urban exploration” is to some extent a misnomer, because the sites are not necessarily in urban area. I devised a planar spectrum to classify and illustrate their types by mapping a set of common categories onto the quadrants.

The vast uncertainties during the exploration imbue the activity with a sense of adventure. Sites are usually wrapped in layers of protection, so finding an access point means a security breach. Due to lack of maintenance, movement on the unstable structures is often a seismic gamble. There could also be unexpected encounters: unfriendly, paranoid dwellers lurking in the dark; surprise motion sensors that dispatch police or security guards without warning. This lingering sense of challenge is what drives curious onlookers away from this hobby. For the ones who stay, the tangible existence at the location, spatially and temporally, nevertheless, evokes a euphoria, a shivering excitement, akin to another world. This sensation is likely triggered by the emancipation from the regulated, constrained, or even monitored, intentionally or inadvertently by others, regime of movement under urban settings. In a bustling crowd, everything is under scrutiny, where “unsociable” activity is demeaned, with the danger of being tagged as “bizarre” or “erratic”. These conventions are thus internalized by the unwitting individual, that no unexpected expression or behavior ever occurs. Abandoned sites are spaces that exist beyond such conventions. They grow interstitially in the absence of urban regulations, as terrain vague, become rightfully obsolete and unproductive, and manifest themselves as spaces of freedom that are an alternative to the lucrative reality prevailing in the late capitalist city. They are anonymous realities.2

Without the designated routes and pattern, abandoned sites, with their crumbled ceilings, leaky drainage pipes, hanging beams, and often cracked walls, present themselves as labyrinths that reconfigure the topology to contradict with our daily experience; previously impassable paths are accessible, whereas the familiar stairways and signs lead to cul-de-sacs. The physical movements forcibly adapt to a more volatile, improvisatory style, yet the sensual affordances remain heterogeneous, varying particularly with the type of sites. The following are three main categories.

-

Industrial Ruins.

The old, once vivid industrial regions are always crowned with despondent names: Rust Belt for the US midwest, Il Triangolo dela Morte (Triangle of Death) for Campania in Italy, Pays Noir (Black country) for coal belt in Belgium and France, etc. A multitude of industrial sites sprawled along the railway, weaving through the roaring steam engines, in a steampunk style. Yet the good old days are gone. They exude a smell of desperation, futility, in the dark and damp corner of history and land, lingering as a scar. They are martyrs of a once-gilded era, figures of the rampant development. Such symbolism is widely employed in the lenses of Chinese directors: movies such as Black Coal, Thin Ice, Piano in a Factory, and The Looming Storm all have their stories settled in the Rust Belt of the Northeastern provinces, and their characters’ fate is correlated with that of the doomed factories. In Black Coal, Thin Ice, the old, dilapidated factory casts a cold and grey tone over the story’s backdrop. It starkly contrasts with the vibrant, yet eerily lurid neons of the dance hall, carving out the contours of a magical realist narrative. I realized that my preference for such movies is rooted in the obsession with the industrial scenes, especially with the collieries, refineries, and steelworks. The colossal machineries, such as the blast furnace, the converters, and gantry cranes, are lurking behemoths, seething in silence. Back then, they were fully operating, slowly and clumsily, but full of strength, with that shaking energy and ominous voice, that no one dares to tame their temper. Now they are silent, static, but this giant amount of power still oozes out from their hulking bodies, creating an irresistible fear. It is electrifying to see such monolithic mass indulging in its obsolescence, being brazenly unproductive, exposing, or even proudly manifesting its own decay.3

-

Private Space.

A cozy, personal, familiar place conjures a very different atmosphere. Houses, theaters, hotel rooms, unlike the metal beasts from industrial ruins, are scenes in our daily life and common practice, and their decay arouses the fear in ourselves, because they provide a showcase, that without proper maintenance, how the ultimate condition of our reliable environment would become. Many such places remain the temporality when they were abandoned; the CDs on the stand, the paper and photos on the desk, plates in the sink, half-eaten bag of chips, all seem to show acquiescence that the routine is merely suspended, that the owner might return at any moment. The stillness of time is laid bare within this stagnant cocoon. The display of an abrupt manner of withdrawal raises fatal fascination for explorers; they are located exactly at spatial coordinates in the space-time reference frame, where the only difference is on the time axis. History never truly fades, as the rising entropy in the closed room inscribes every fragment of the past. That aligns with people’s investigative penchant for finding evidence of existence.

Schools, hospitals, or even sanatoria, on the other hand, may trigger horror in their abandoned state. This horror is not as tightly related to their original functionalities; it is more of a direct consequence from their liminal nature, and the so-commonly-perceived supernatural presence. As someone with a materialist perspective, the former concept is apparently a better explanation. Liminal space is a state of transition, a space in-between, typically with a surrealistic touch of disorientation. The corridors, stairwells, hallways are transitional places connecting functional spaces, once devoid of people, they appear eery and forlorn. Their abandoned states adds an additional layer of purposelessness; the corridor no longer leads to a destination with defined purpose, but to the elusive, dark unknown.

-

Open-Air Relics.

From ancient villages to modern day bunkers, relics are remains of history, in a sense that they either served a special, yet now-obsolete functionality, or lost their importance, gradually withered until buried in time. The abandonment took place on an earlier time scale, and their decay is now in its final stage, where past usage is reconstructed through imagination and historical footnotes. Relics lie on the border of definition of urban exploration, and is a good introductory course of newcomers. Take a walk through the relics, away from the crowds. In a site like Machu Picchu or Easter Island, the spiritual resonance with those who labored and lived here centuries ago might strike your soul. When the abandonment is more recent, this feeling intensifies, hence the irresistible allure of urban exploration. Nowadays, places like Machu Picchu and Easter Island are never referred to as “abandoned sites” or “ghost towns”, and more specifically, never in the history either. The notion of abandonment, as understood today, is largely a byproduct of urban productivity within the framework of capitalism—something that did not exist in relics’ society. Likewise, modern-day bunkers are not truly “abandoned”, as their purpose is inherently tied to a specific moment in time.

This concludes the brief introduction of urban exploration. The 16th street railway station, with years of advocacy from Oakland Heritage, finally gained recognition from National Register of Historic Places. Multiple reactivation plans have been proposed, and it will likely revive soon. But not all abandoned sites receive this recognition. Many of them either remain forgotten, slowly covered in graffiti and crumbling under vandalism, or are demolished once the authorities grow tired of such activities. This is the life cycle of manmade architecture. There are thousands of them dying, and thousands being renovated and reborn every day. The urban complex is a giant organism where growth and decay occur simultaneously. So is everything else. Being able to take a peek at their post-mortem stage is a rare and cherished privilege. It is also our responsibility to document with meticulous care, regardless of what the state might be. This is why we love urbex.

-

Elizabeth Blasius, Urban Exploration as Creative Practice, MAS Context, 2024. ↩

-

SOLÀ-MORALES RUBIÓ, Ignasi de, Presente y futuros. La arquitectura en las ciudades. In AA. VV., Presente y futuros. Arquitectura en las grandes ciudades, Barcelona: Collegi Oficial d’Arquitectes de Catalunya / Centre de Cultura Contemporània, 1996, 10-23. ↩

-

Ninurta, Walking in the post-apocalyptic world, https://www.youtube.com/@Ninurta_Urbex. ↩

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: