LLM Study Notes III: Post-Training

SFT (Supervised Finetuning)

This is the most intuitive first step after getting a pre-trained model, that is able to auto-regressively generate tokens that make sense. The model now has the ability to make full sentences, continue speech, or “understand the meanings” of questions, but still requires guidance to behave “normally” in human eyes. We can enforce the model to generate what we want, by feeding it such data, so it’s not just blindly spitting out words, but also generating texts in a way that we expect it to be, hence the “supervision”. Take the simplest example of QA pairs: the prompt (prefix for the decoder) is a question, and expected prediction sequence is the answer. We can compute the loss between actual answer from the model and the ground truth answer, and update the model:

just like in pre-training, it uses teacher forcing, so it’s basically feeding in the selected [Q + A] sequence. This is the same format used in pre-training, just with some special tokens separating question and target answer. The inputs are like

\[\text{<soq>}, q_0, q_1, ..., q_{n-1}, \text{<soa>}, a_0, a_1, ..., a_{m-1}\]where the model outputs

\[\hat{q}_0, \hat{q}_1, ..., \hat{q}_{n-1}, \text{<soa>}, \hat{a}_0, \hat{a}_1, ..., \hat{a}_{m-1}, \text{<eos>}\]The only difference is we mask off the question part, and only compute cross entropy loss between logits of generated answer tokens and ground truth answer tokens.

For proper full post-training SFT, the entire model is finetuned in this fashion end-to-end. For some specific tasks or small datasets, parameter-efficient finetuning techniques (PEFT) such as LoRA, prefix-tuning are also used, which freezes some layers in the LLM and not changing parameters across the entire model.

What’s the scale of the SFT dataset, and how many labelers/crawled data from internet?

Reward Model

In preparation to make the model ready for deployment, just handwaving cramming it with preferred data is not sufficient. There should be at least some metrics to score the model response. One way to do that is training a reward model, that takes a [prompt, response] sequence and generates a scalar score. The training of the reward model involves heavy human labeling, which is the “human feedback” part in RLHF. The labeler’s job are not giving scores—it would be too subjective and unintuitive to give absolute scores on a scale. They simply compare two responses model generated from one prompt, and labels which one they prefer. This way the ranking of multiple responses can be confirmed. The training signal comes from this A/B comparison:

score1 = RM(A1 | P) # model generates score of answer 1, given prompt

score2 = RM(A2 | P)

pref = sigmoid(score1 - score2) # if score 1 higher, prefers answer 1

loss = binary_cross_entropy(pref, label.float()) # compare with actual label for the loss

The reward model is usually simple as one reward MLP head attached on the embeddings output from LLM, and LLM parameters are obviously frozen during reward head training.

Reinforcement Learning w Human Feedback (RLHF)

The RL part is essential to achieve a human-like performance from the model, and it combines the previous SFT and reward model. The RL agent, or the initial policy, starts from the SFT model. The reward model is crucial to give feedback to the agent for policy updates. There are a few common setup, widely adapted by various finetuning methods.

Start from simple case where one episode is one prompt —> one answer. This is the most common and intuitive approach. Different from regular RL, for LLM we need to note

- \(r_t = 0\) for all steps, except for \(r_T\) which equals to \(\text{RM}(s_T)\). This makes the reward signal extremely sparse.

- usually the response is punished by how much updated policy deviates from the original (SFT) reference policy. This is reflected in the reward signal, which is commonly set as

- There is no state transition, no external environment dynamics, and the new state is just the next token (action) concatenated with previous states/actions (prefix).

- The sequence log-prob \(\log\pi_\theta(y\mid x)\) is very useful in policy gradient algorithms. The occurrence probability for a sequence of tokens is \(p_\theta(\tau) = p_\theta(x_0)\cdot p_\theta(x_1 \mid x_0)\cdot p_\theta(x_2 \mid x_0, x_1)\cdot ...\), which becomes \(\log p_\theta(\tau) = \sum_{t=1}^T\log p_\theta(x_t \mid x_{<t})\) after taking log. The sequence log-prob in implementation is just log_softmax on the logits (logits are the raw scores output from model before softmax).

Now we can check some popular algorithms used in RL for LLM.

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)

This algorithm was devised in 2017 and has been since popular in all branches of RL. It is widely used in fields such as robotics due to its intrinsic stability in training. It was adapted by InstructionalGPT at some early versions of GPT series, and contains an actor-critic network.

The actor is the SFT model that samples actions by policy. The policy update is nothing special, and no different from original PPO algorithm:

\[\begin{align}r_t(\theta) = \frac{\pi_\theta(a\mid s)}{\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(a\mid s)} &=\exp(\log\pi_\theta(a_t\mid a_{<t}, s) - \log{\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}}(a_t\mid a_{<t}, s))\\ L(\theta) &= \mathbb{\hat{E}}[\min(r_t(\theta)\cdot \hat{A}_t, \text{clip}(r_t(\theta), 1-\epsilon, 1+\epsilon) \hat{A}_t)] \end{align}\]where \(r_t(\theta)=\frac{\log\pi_\theta(a_t\mid a_{<t}, s)}{\log\pi_{\theta_\text{old}}(a_t\mid a_{<t}, s)}\) tells PPO how much more/less likely the new policy is to output the given token compared to the old policy. The log probabilities of each token are just log softmax on predicted logits.

Now let’s look at the critic network. This is for me the most challenging part. It basically involves how to compute the crucial \(A\) advantage value used for the policy update. We know advantage is how much better the action behaves than the baseline, from the definition:

\[A(s_t, a_t) = Q(s_t, a_t) - V(s_t)\]\(Q(s, a)\) means the expected return from \(s\) if \(a\) is taken; \(V(s)\) means the expected return from \(s\) following normal policy; then \(A(s, a)\) means the relative improvement when choosing \(a\).

Both terms on the RHS are unknown. What can we do about them?

Remember we are training an actor-critic style network. What if we train both \(Q\) and \(V\) networks? This creates redundancy, because it is equivalent to train one advantage network \(A\); but we cannot do that—because this causes circular dependency, as actor network (policy) is dependent on \(A\) as well. So our choice is to train either \(Q\) or \(V\). In the early days of reinforcement learning, there are some ground breaking works on training \(Q\) network—Q-learning and DQN are good representative methods. However to train Q, we need to condition on both the state and action, and the action set here is the total number of tokens defined, which blows up the state-action space. A much simpler and cheaper option is to train the value function network \(V\). This V-network becomes our critic.

We have decided to train \(V\) as our critic network, then what do we do about \(Q\)? There are two methods that approximate Q value:

-

Monte Carlo: use observed return \(R_t\) directly.

\[\begin{equation}\hat{Q}(s_t, a_t) = \sum_{k=0}^{T-t}\gamma^{k}r_{t+k}\end{equation}\]This is basically expanding the full rollout and uses the return at the end of the entire trajectory, which is equivalent to use the scalar score from trained reward model given current \(s\) (prompt + full response). This will assign the same Q value for every single token in that response, because the reward is only given at the end of the sequence. It is unbiased because it’s not using the value estimation, but it has very high variance, since a different action may change the course of the trajectory greatly, causing a very different return at the end.

-

Temporal Difference (TD-1) target: bootstrapping with value network.

\[\begin{equation}\hat{Q}(s_t, a_t) = r_t + \gamma V_\phi(s_{t+1})\end{equation}\]This is basically relying on the value network to estimate the transition. This method has low variance because it’s using the value network, but has high bias, since value network can have incorrect estimation and kept giving wrong Q values.

Is there a way to mitigate the disadvantages of those two extreme estimation methods while keeping their advantages? We can see Monte Carlo is picking up returns from all steps, while TD only picks current step. The formulation that mathematically describes the range between those two extremes is \(k\)-step return:

\[\begin{equation}R_t^{(k)} = \sum_{i=0}^{k-1}\gamma^ir_{t+i} + \gamma^kV(s_{t+k})\end{equation}\]which estimates the return by rolling forward to step \(t + k\). When \(k\) goes from 0 to infinity, it goes from TD-1 to Monte Carlo. To get a good estimation of all these returns, one natural approach is to assign a coefficient for each time step:

\[\bar{R}_t = \sum_{k=1}^\infty c_kR_t^{(k)}\]In his 1988 paper Temporal Difference Learning with Eligibility Traces, Sutton made a brilliant choice of these coefficients: using geometric distribution, by setting \(c_k = (1-\lambda)\lambda^{k-1}\):

\[\hat{R}_t^{\text{TD}(\lambda)} = (1-\lambda)\sum_{k=1}^\infty \lambda^{k-1}R_t^{(k)}\]This way all coefficients add to one, and when \(\lambda\rightarrow0\), it evaluates to Monte Carlo, when \(\lambda\rightarrow1\), it evaluates to TD-1. This new mixture estimation of return value is called TD(\(\lambda\)).

How does this connect to our advantage function? Let’s start again from TD-1 and plug in the estimation into advantage definition directly, to see what we have:

\[\delta_t^V = [r_t + \gamma V(s_{t+1})] - V(s_t)\]This is called TD-error, which means the surprise model got by taking this action. This can also be used as the training signal for the value network, which we will mention later. If we imitate what we did above, we get \(k\)-step TD-error:

\[\begin{equation}\delta_{t+k}^V = r_{t+k} + \gamma V(s_{t+k+1}) - V(s_{t+k})\end{equation}\]To get the total error over \(k\)-steps, accumulate \(\delta\) by \(\gamma\) discount factor:

\[\begin{align}&\delta_t^V + \gamma\delta_{t+1}^V + ... + \gamma^K\delta_{t+k}^V =\nonumber\\ &[r_t + \gamma V(s_{t+1}) - V(s_t)] + \gamma[r_{t+1} + \gamma V(s_{t+2}) - V(s_{t+1})] + ...=\nonumber\\ &r_t + \gamma r_{t+1} + ... + \gamma^{k-1}r_{t+k-1} + \gamma^kV(s_{t+k}) - V(s_t)\nonumber\end{align}\]we can see the intermediate \(V(s_{t+i})\) terms all got cancelled out. This is the \(k\)-step estimator of the advantage function:

\[\begin{equation}\hat{A}_t^{(k)} = \sum_{l=0}^{k-1}\gamma^l\delta_{t+l}^V = \sum_{l=0}^{k-1}\gamma^lr_{t+l}-V(s_t)\end{equation}\]Now we apply the geometrically weighted mixture of \(\hat{A}_t^{(1)}, \hat{A}_t^{(2)}, ..., \hat{A}_t^{(k)}\), with \(k\rightarrow\infty\), just like how we got TD(\(\lambda\)), which gives the Generalized Advantage Estimator, \(\text{GAE}(\gamma,\lambda)\):

\[\begin{align}\hat{A}_t^{\text{GAE}(\gamma,\lambda)} &:= (1-\lambda)(\hat{A}_t^{(1)} + \lambda\hat{A}_t^{(2)} + \lambda^2\hat{A}_t^{(3)} + ...) \nonumber\\&=(1-\lambda)(\delta_t^V + \lambda(\delta_t^V+\gamma\delta_{t+1}^V)+\lambda^2(\delta_t^V+\gamma\delta_{t+1}^V+\lambda^2\delta_{t+2}^V)+...)\nonumber\\&=(1-\lambda)(\delta_v^V(1+\lambda+\lambda^2+...)+\gamma\delta_{t+1}^V(\lambda+\lambda^2+\lambda^3+...)+\nonumber\\ &\gamma^2\delta_{t+2}^V(\lambda^2+\lambda^3+\lambda^4+...) + ...)\nonumber\\&=(1-\lambda)(\delta_t^V(\frac{1}{1-\lambda})+\gamma\delta_{t+1}^V(\frac{\lambda}{1-\lambda})+\gamma^2\delta_{t+2}^V(\frac{\lambda^2}{1-\lambda})+...)\nonumber\\ &=\delta_t^V+\gamma\lambda\delta_{t+1}^V+(\gamma\lambda)^2\delta_{t+2}^V+...\nonumber\\&=\sum_{l=0}^\infty(\gamma\lambda)^l\delta_{t+l}^V\end{align}\]Note we have \(\lambda\in[0, 1]\), hence \(1+\lambda+\lambda^2+... = \frac{1}{1-\lambda}\), and so on. This is the \(\lambda\)-weighted view of GAE, which expands all TD-errors for deduction. There is another view that uses the geometric distribution of \(A_t^{(k)}\) directly:

\[\begin{align}\hat{A}_t^{\text{GAE}(\gamma,\lambda)}&=(1-\lambda)\sum_{k=1}^\infty\lambda^{k-1}A_t^{(k)}\nonumber\\&=(1-\lambda)(\sum_{k=1}^\infty\lambda^{k-1}\sum_{l=0}^{k-1}\gamma^l\delta_{t+l}^V)\nonumber\\&=(1-\lambda)\sum_{l=0}^\infty\frac{(\lambda\gamma)^l\delta_{t+l}^V}{1-\lambda}\nonumber\\&=\sum_{l=0}^\infty(\gamma\lambda)^l\delta_{t+l}^V\end{align}\]This advantage is by definition, then error between estimated \(V_\phi\) and value function target \(V\). This way we can find the training signal for the critic network:

\[V_t^G = V_\phi(s_t) + \hat{A}_t^{\text{GAE}}\]this achieves the bootstrapping of an accurate value function estimation. The full training loop looks like this:

- Roll out the entire sequence under current policy \(\pi\)

- Compute \(\hat{A}_t^{\text{GAE}}\) with returns from reward model and current \(V_\phi\)

- Use this advantage value \(A_t\) to update both actor (policy) and critic (value network)

- Repeat the process until convergence

The value network \(V_\phi\), is also a head attached to decoder embedding outputs, just like the reward model. Over training loops it is pulled towards the correct side by signal sent in advantage values, which uses the reward model outputs for returns. Let’s look into the details, keeping in mind the special features of LLM RL, that reward is only given at the end of the sequence, when \(t = T\):

\[\begin{align}\hat{A}_t^\text{GAE} &= \sum_{l=0}^\infty(\gamma\lambda)^l\delta_{t+l}^V\nonumber\\&=\sum_{l=0}^{T-t}(\gamma\lambda)^l(r_{t+l} + \gamma V(s_{t+l+1}) - V(s_{t+l}))\nonumber\\&=\sum_{l=0}^{T-t-1}(\gamma\lambda)^l(\gamma V_\phi(s_{t+l+1})-V_\phi(s_{t+l})) + (\gamma\lambda)^{T-t}(r_T-V_\phi(s_T))\end{align}\]Direct Preference Optimization (DPO)

Remember with PPO, it takes a separately trained reward model and computationally expensive RLHF process to align the model with human preference. The point of DPO is to simplify this process and achieve the same effect by training directly on the labelled preference data. It captures the reward model implicitly by learning the preference data as a supervised classification problem, instead of explicit reward model + RL. DPO is used for later GPT series, such as GPT-4o. The deduction of DPO updates are quite math-intense and involved, and I will just summarize some key points here. The policy training objective is to maximize

\[\mathcal{L} = \mathbb{E}_{(x,y_w,y_l)\sim D}[\log\sigma(\beta\log\frac{\pi_\theta(y_w\mid x)}{\pi_{ref}(y_w\mid x)}- \beta\log\frac{\pi_\theta(y_l\mid x)}{\pi_{ref}(y_l\mid x)})]\]The authors continued to show the link between DPO and reward model. First they defined a normalization partition function

\[Z(x) =\sum_y\pi_{\text{ref}}(y\mid x)\exp(\frac{r_\phi(x, y)}{\beta})\]where \(r_\phi\) is the reward model. The optimal aligned policy model is

\[\pi^*(y \mid x) = \frac{\pi_{ref}(y\mid x)\exp(\frac{r_\phi(x,y)}{\beta})}{Z(x)}\]and

\[r_\phi(x, y) = \beta[\log\frac{\pi^*(x\mid y)Z(x)}{\pi_{\text{ref}}(y\mid x)}+\log Z(x)]\]It also discussed the Bradley-Terry model (for pairwise data) as well as the more general Plackett-Luce model (for ranking with more than two data points). In summary the training loop looks like this:

- Given prompt, preferred response, loser response \((x, y_w, y_l)\), compute the sequence log-prob under policy \(\log\pi_\theta(y \mid x)\), as well as the sequence log-prob for frozen reference policy.

-

Compute the DPO score for each response, here for the winner and loser:

\[s_\theta(y \mid x) = \beta(\log\pi_\theta(y \mid x) - \log\pi_\text{ref}(y \mid x))\] -

Compute the pairwise log-sigmoid objective, and minimize this loss by back propagation.

\[\mathcal{L}(x, y_w, y_l) = -\log\sigma(s_\theta(y_w \mid x) - s_\theta(y_l \mid x))\]

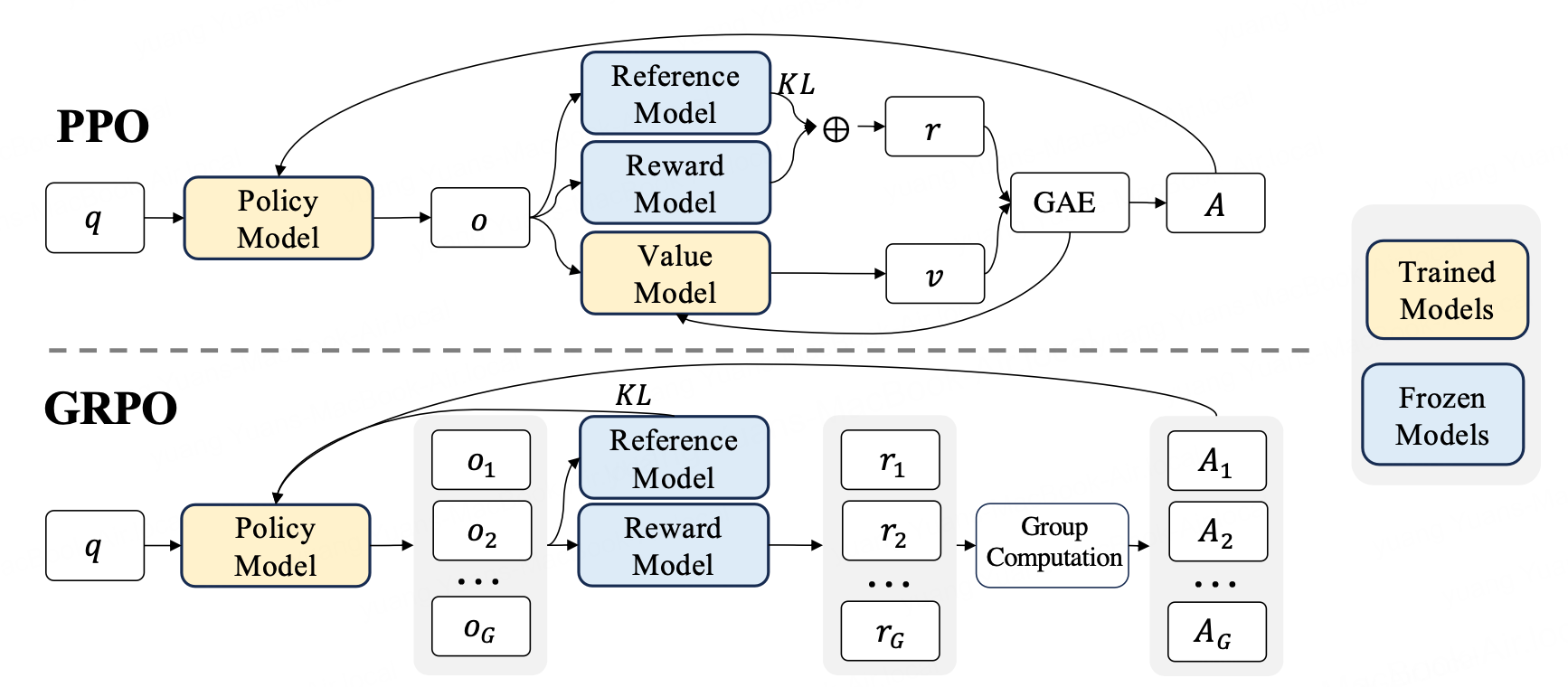

Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO)

GRPO is devised by DeepSeek and achieves stunning performance with significantly less parameters and complexity, thanks to its omission of critic network. Just like PPO, GRPO also uses advantage values to update the policy model, but instead of using a separate value model (critic) to estimate GAE over one output sequence to get advantage, it makes use of a group of output sequences \(s\) and compute their return values \(R_i=\text{RM}(p, s_i)\), which are averaged to get a baseline score \(\bar{R} = \frac{1}{G}\sum_{j=1}^GR_j\), used to compute the advantage \(A_{i} = R_i - \bar{R}\) for each of them. This comparison is well-illustrated by the figure in the original paper, attached below.

There are a few more subtle points not captured by the figure:

- The KL divergence penalty is not in the GRPO reward, but directly to the loss; it also uses a different form from PPO and is guaranteed positive.

- The advantage \(A_{i}\) here is sequence-level advantage, where reward is only given at the end of each sequence. In the original paper, DeepSeek call this outcome supervision RL and normalize it by \(\tilde{R}_i=\frac{R_i - \bar{R}}{\sigma(R)}\); however, the paper views it as insufficient, because the advantage is broadcasted to each token, so that all tokens are updated in the same direction. The paper then brings up process supervision RL, which assigns per-token, or per-step reward to overcome this problem. It would require a process reward model to give reward at each step, and they are normalized in the same way by \(\tilde{r}_{i,j} = \frac{r_{i,j} - \bar{R}}{\sigma(R)}\), where advantage \(A_{i, j}=\sum_{j\geq t}\tilde{r}_{i,j}\). This process reward model is claimed to be heuristic functions.

- The critic-free model is in nature less stable in training, compared to actor-critic models. GRPO has this weakness, and is very sensitive to the batch size, because less data means noisier baseline. In practice with large batch size and sufficient amount of data, GRPO can overcome this weakness.

Regarding the second point, one question I had was, why not use similar GAE method to distribute sequence-level reward back to each token? The problem is PPO has a trained critic network that approximates the value function, which enables the GAE. GRPO avoids this critic network, and does not have such signal from the group of outputs. The process reward model or function is thus necessary.

Reinforcement Fine-Tuning (RFT)

RFT is claimed to be used by Anthropic Claude. It skips reward model in a different way than does DPO. It shares the same policy update object with PPO, and for the value model update, it adds an additional clipping term just like for policy, to stabilize the critic model training:

\[\mathcal{L_V}(\phi) = \frac{1}{2}\mathbb{E}_{\mathbf{e}\sim\pi_\text{old}}[\max(\|V_\phi(s_t)-\hat{R}_t\|^2, \|\text{clip}(\hat{R}_t-V_\phi(s_t), \hat{A}_t-\epsilon, \hat{A}_t+\epsilon)\|^2)]\]The policy model in RFT does not rollout data like in regular RL. Instead, these are human-labeled preference data, the same ones that can be used to train reward model. However RFT skips the reward model training part: it focuses on Chain-of-Thought and extracts answers from the process, which are used to compute the advantage value for the future training process. It is also a soft blend between PPO and SFT, where PPO is pure RL with reward values from another model, and SFT is equivalent to a binary reward assignment: 0 for bad response, 1 for good response. RFT takes a partial reward as middle ground. It is actually very similar to the RLT (reinforcement learning teachers) distillation method, which uses the teacher models as heuristics to evaluate the policy rollouts.

Conclusion

The full post-training workflow contains other alignment and tuning techniques, such as rejection sampling, chain-of-thought, thinking mode fusion, and so on. They are devised to improve specific abilities of the models, such as reasoning, instruction-following, and agentic responding. It is the differing ways these techniques are employed that shape the unique personalities of each model, imprinting them with distinctive technological hallmarks of their developers. This study note does not go into those details. As a conclusion, the paper All Roads Lead to Likelihood proves theoretically that all such fine-tuning methods such as DPO, SFT, and RFT are mathematically equivalent.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: